The Epic Journey of India’s Agrochemical Ascent

India’s story after independence is often told through political and industrial changes. But its most profound transformation began with a […]

Navneet Singh

Monday October 13th, 2025

India’s story after independence is often told through political and industrial changes. But its most profound transformation began with a single reality: the struggle to feed its own people. In the years after 1947, a nation of farmers faced severe food scarcity. This was famously called a “ship-to-mouth” existence. Grain ships from overseas were a lifeline. However, they were also a source of national humiliation. They were a constant reminder that India remained deeply vulnerable. This reality set the stage for an epic journey. It forced the country to rethink its relationship with the land. It began a revolution that would eventually ripple across the globe.

The first step in this monumental shift was not a technological one. It was social and political. Colonial rule had left India’s agricultural land in a highly unequal state. A feudal land tenure system prevailed. A small group of intermediaries, like zamindars and jagirdars, held vast tracts of land. Their main goal was not to improve the land or boost productivity. Their goal was to extract maximum rent from tenant farmers. This system created a cycle of low yields and rural poverty. It was a major hindrance to agricultural development. It was clear that before any new technologies could be introduced, the foundation of land ownership had to be reformed.

In response, post-independence policymakers launched ambitious land reforms. Their goal was to create a more equitable agrarian society. The most critical initiative was the abolition of these intermediaries. This directly transferred land ownership to the farmers who worked it. This crucial step gave farmers a powerful incentive. They could now invest their labor and resources to improve their land. This was a luxury previously unavailable to them. The government also implemented land ceiling laws. These laws fixed the maximum size of land an individual could own. The goal was to redistribute surplus land to the landless. It also aimed to reduce the concentration of wealth and power. These reforms faced hurdles. For example, large landlords used legal loopholes to evade the laws and evict tenants. However, the reforms still laid the essential groundwork for future growth. The success was most evident in states like Kerala and West Bengal. In these places, the political will was strong enough to ensure effective implementation.

The stage was now set for the next phase: a technological revolution. This was the moment when India’s agricultural strategy moved beyond structural reforms to scientific intervention. This movement was championed by Dr. M.S. Swaminathan. He is often called the “father of the Indian Green Revolution.” Dr. Swaminathan had a personal experience with the 1943 Bengal Famine. This experience left a deep mark on him. He saw that India’s agricultural productivity was stagnant. This was due to outdated methods and a heavy dependence on unpredictable monsoons. He saw a path forward. He introduced high-yielding variety (HYV) seeds, especially for wheat and rice. These seeds had been developed in Mexico by Nobel laureate Norman Borlaug.

The Green Revolution was a comprehensive toolkit for modernizing agriculture. It not only introduced HYV seeds, but also emphasized the widespread use of synthetic fertilizers. These new seeds absorbed far more nitrogen than their native counterparts. The use of pesticides and mechanized tools also became more common. This protected crops from pests and diseases. It also boosted overall yields. This technological leap, built on the foundation of land reforms, created a profound and rapid change. Within just a few years, India’s grain output skyrocketed. After just one year of using the new seeds, grain production grew by 5 million tons. By 1971, the total yield reached 104 million tons. This was a 40% increase from the drought years of 1965-66. This success allowed the government to establish buffer stocks. This protected the nation from future food shortages. The country had finally achieved food self-sufficiency. It successfully transitioned from a food-scarce nation to a food-exporting one. In doing so, it laid the foundation for its modern agrochemical industry.

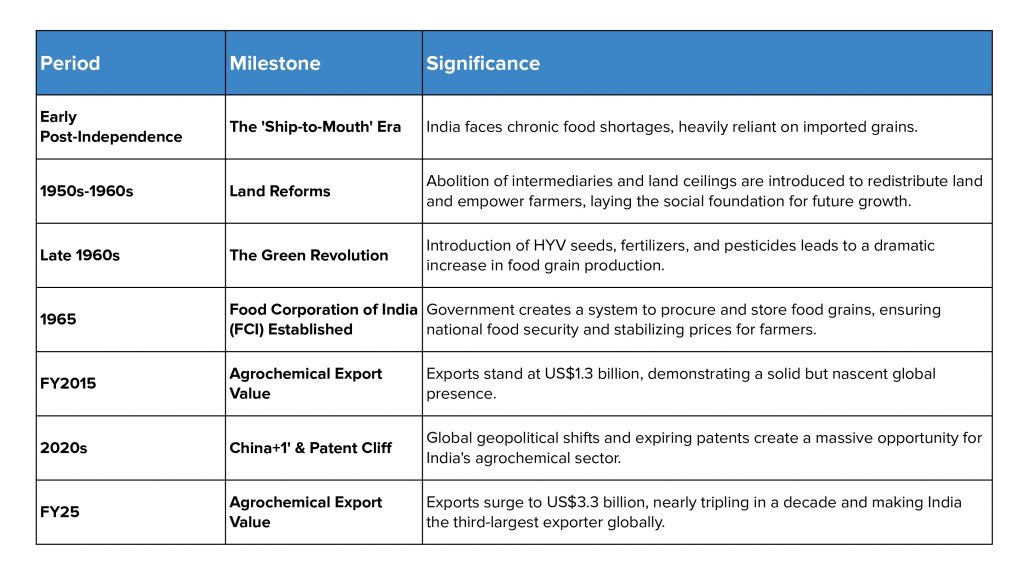

This transition from self-sufficiency to a net exporter can be seen in the following timeline of key milestones.

The Green Revolution was a turning point. However, it also had complexities and contradictions. For decades, the nation faced a paradox of progress. It had solved its food security problem. But its agricultural sector was still haunted by persistent challenges. A large majority of the population, about 65% as of the 1990s, remained dependent on the sector. This was despite a significant decline in agriculture’s contribution to national GDP. The land reforms were transformative, but not a complete solution. The number of marginal landholdings (less than one hectare) continued to grow. This made mechanization and efficient farming difficult. The unpredictability of farming also remained. It was still heavily reliant on monsoons. There was also an uneven distribution of modern technology and irrigation.

The agrochemical industry, in particular, faced a unique set of hurdles. A critical vulnerability remains a heavy dependence on imports. These imports include technical-grade active ingredients and key intermediates. About 50% of these essential inputs come from a single country: China. This reliance exposes India’s agrochemical supply chain to strategic risks. These risks range from disruptions due to geopolitical tensions to price spikes and shortages from factory shutdowns in China. The industry’s journey to self-reliance is incomplete without addressing this core dependency.

Another significant obstacle is the complex and costly regulatory environment. The registration process for new agrochemical molecules in India is often viewed as lengthy and intricate. Only the largest corporations can afford to navigate this maze. This stifles innovation. It also delays new products from reaching the market. As of late 2020, India had only 273 molecules registered for use. This is a stark contrast to the 473 in the European Union and 527 in Japan. The lack of a strong legal framework for data protection also discourages companies. Both international and leading domestic companies hesitate to introduce new, proprietary molecules in the country. They fear that competitors will quickly get approval for similar products. This regulatory bottleneck is a key reason India has become a leader in generic agrochemicals. It has not yet become a global innovator of new molecules.

This challenge is compounded by a significant gap in research and development (R&D) investment. Overall, the Indian agrochemical industry spends only 1-2% of its turnover on R&D. This is a fraction of the 5-10% invested by companies in developed countries. While some leading players, like PI Industries, have shown impressive growth by commercializing new products and investing in R&D, this remains an exception. This lower R&D spend means the industry is well-positioned to capitalize on off-patent, multi-source generics. But it is not yet prepared to move up the value chain to create new, high-margin, proprietary products. This would secure a dominant global position in the long term.

These challenges were recently put to the test. Despite a decade of steady growth, India’s agrochemical exports saw a sharp decline. They fell by nearly 22% in FY24. This sudden drop was not a sign of fundamental weakness. It was a reflection of broader global market forces. The decline was mainly due to widespread global destocking. This was a post-pandemic inventory correction. It was also due to heightened price competition from China. While a setback, this period demonstrated the industry’s newfound maturity. It is now large enough to be affected by the cyclical pressures of the global economy. Importantly, a moderate rebound is already expected in FY25. This shows that the underlying structural drivers of India’s growth remain intact.

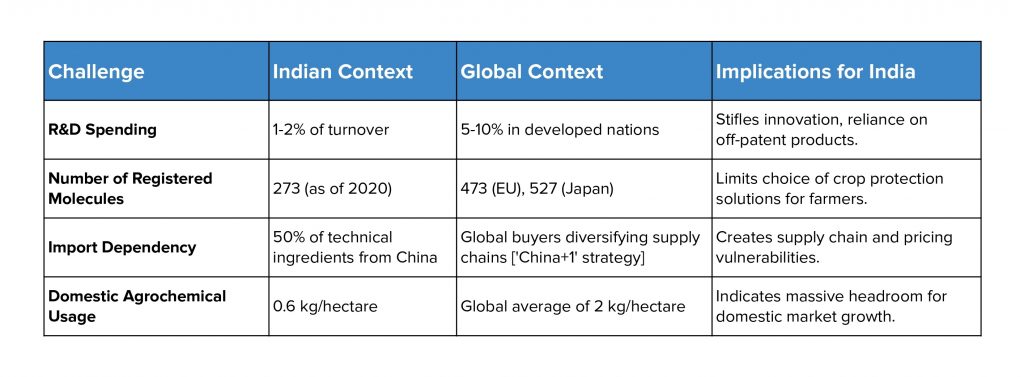

The challenges facing the industry can be more clearly understood through a global comparison.

The recent success of India’s agrochemical sector is the culmination of its historical journey. It is also a result of its ability to turn challenges into opportunities. The country’s agrochemical exports have nearly tripled in a single decade. They soared from US1.3billioninFY15toastaggeringUS3.3 billion in FY25. This phenomenal growth has made India the world’s third-largest agrochemical exporter. It is behind only China and the United States.

This ascent is not the result of a single policy. It is a “perfect storm” of converging global and domestic forces. On the global stage, two powerful trends have acted as significant tailwinds. The first is the “China+1” strategy. This is a geopolitical and supply chain pivot. Global buyers are actively diversifying their sourcing away from China due to growing trade tariffs and strict environmental norms. India has emerged as the most logical and reliable alternative. This is because of its cost-effective manufacturing, skilled talent pool, and a robust chemical industry.

The second major force is the global “patent cliff.” Products worth a staggering US$4.2 billion are going off-patent between 2023 and 2025. This is a massive opportunity for Indian manufacturers. They can produce high-margin generic molecules. This is a market segment where they have already established a commanding 80% share. This strategic advantage plays directly to India’s strengths. These strengths are cost-effective manufacturing and technical expertise.

The domestic engine of growth has been equally crucial. The government’s strategic focus on ‘Make in India’ and ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ has been instrumental. It has boosted domestic production and reduced import dependence. The industry has actively engaged with these policies. Bodies like the Agro Chem Federation of India (ACFI) have urged the government to introduce a Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme. They have also requested tax holidays. Such measures are designed to incentivize large-scale domestic manufacturing. They also strengthen the sector’s global competitiveness.

Leading Indian companies are not just waiting for policy changes. They are taking proactive steps to consolidate their position. They are investing heavily in “backward integration.” They are building in-house manufacturing capabilities for key technical ingredients. This lessens their reliance on Chinese imports. Companies like UPL and PI Industries have seen remarkable growth. They have focused on strategic reinforcement, product innovation, and expanding their portfolios. This forward-thinking strategy is not just about competing on price. It is about securing supply chains and moving up the value chain.

A key indicator of the government’s commitment is the “Fast Track Applications” policy for export-only pesticides. The domestic registration process for agrochemicals is complex. However, the government has created a simplified process for products intended exclusively for export. This system processes applications from firms with a confirmed export order on a top priority basis. It issues a registration certificate within five working days. This streamlined approach demonstrates a clear understanding of the agrochemical sector’s dual role. It ensures safety and efficacy for the domestic market. It also prioritizes speed and efficiency to facilitate global trade.

The shift to an export-driven market has been the most significant structural change for the sector. In FY24, the domestic agrochemical market was valued at about Rs. 69,000 crore (US$7.82 billion). A majority of the market’s value, 51%, was generated by exports. Domestic consumption accounted for the remaining 49%. This moment signifies that the industry’s primary growth engine is no longer dependent only on the domestic agricultural sector. It is now inextricably linked to its ability to compete on the world stage.

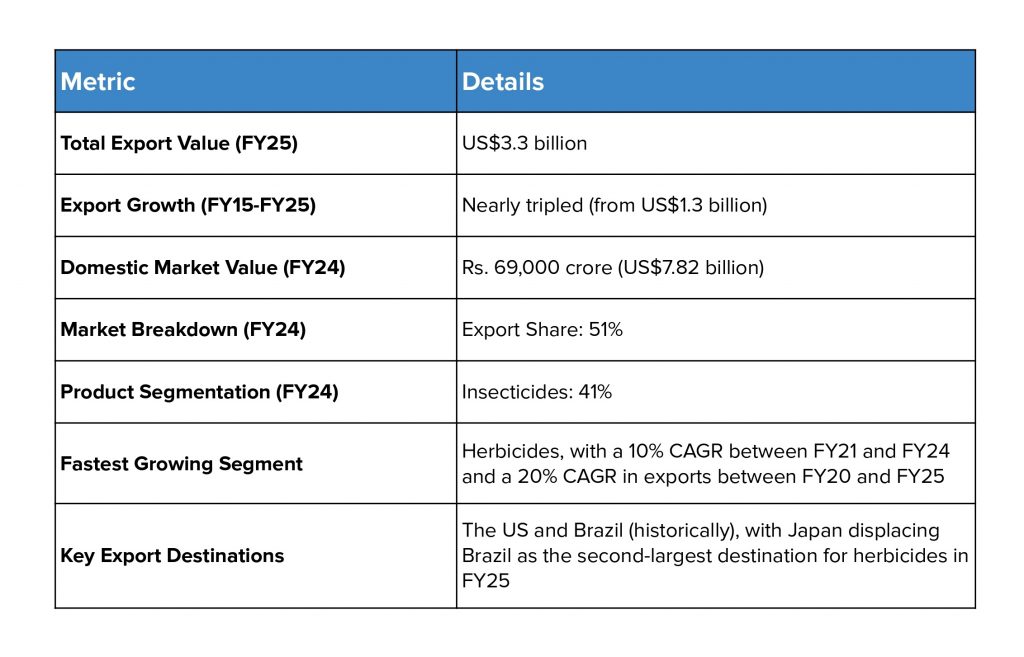

The following table provides a snapshot of the Indian agrochemical market’s performance. It highlights its recent achievements and key drivers.

India’s agrochemical sector has reached a pivotal juncture. It has moved from a domestic necessity to a global player. The current growth is robust. It is fueled by the “China+1” strategy and the global patent cliff. But its long-term dominance depends on its ability to move beyond a “fast-follower” generic model. It must foster indigenous innovation. To achieve this, the industry must address key challenges that have long constrained its potential.

First, a concerted effort to boost R&D investment is imperative. The industry’s current spending of 1-2% of its turnover on R&D is not sufficient. It cannot develop new, proprietary molecules that will sustain growth beyond the current patent cliff. The government can play a crucial role. It can implement the Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme that the industry has advocated for. This scheme could target critical active ingredients and intermediates that are currently imported in large volumes. This would not only incentivize backward integration. It would also encourage public-private partnerships to accelerate the development of new, sustainable crop protection solutions.

Second, streamlining the regulatory landscape is essential. This is needed to unlock the next phase of expansion. Simplifying the complex registration process would significantly encourage companies to introduce new molecules in India. A strong legal framework for data protection would also help. This would attract foreign investment and technology transfer. It would also ensure that Indian farmers have timely access to the latest crop protection solutions. These solutions are often more efficient and safer to use.

Finally, the industry must focus on strengthening micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs). These are crucial for enhancing India’s overall global competitiveness. Providing these smaller enterprises with access to capital, technology, and export opportunities would broaden the industry’s base. It would also create a more resilient ecosystem. The government can create “plug-and-play” industrial parks. These parks would have streamlined environmental clearances and efficient logistics. This would further reduce the cost of doing business. It would encourage investment across the entire value chain.

By building on its historical foundation and strategically addressing these challenges, India’s agrochemical sector can consolidate its recent gains. It can transform into a global manufacturing and innovation hub. This would not only ensure national food security. It would also establish India as a vital and indispensable pillar of the world’s future food supply chain.

In this new era, the focus is shifting from simply producing more to producing better and smarter. This is where companies like Gramophone are leading the charge. They are spearheading a revolution by creating a seamless, one-stop solution for all agricultural needs. By integrating advanced technology, timely agronomy-led advice, and providing access to high-quality inputs, Gramophone is helping farmers achieve better yields and sustainable growth. Through its extensive network of agri-retailers and franchise shops, the company provides genuine crop protection, crop nutrition, seeds, and hardware.

Gramophone’s mission is to bridge the information gap in agriculture, empowering farmers with localized crop advisories, weather updates, and tailored farming practices. This integrated approach ensures that every farmer can make informed decisions, enhance their productivity, and secure a sustainable income. As India continues its ascent as a global agrochemical powerhouse, it’s this blend of cutting-edge technology and a deep understanding of farmer needs that will fuel the next wave of growth and cement its place as a leader in the global agricultural landscape.